The Chemically-Enabled User Interface: An Introduction to Leafcutter

ChemWriter is a 2D chemical structure editor for the Web. Because it's written in Java and uses both the Swing and Java2D APIs, ChemWriter could be plugged into a variety of chemically-enabled user interfaces deployed within a browser, on the desktop, or in other contexts. The availability of this kind of developer tool would open the door to a large new area of interactive cheminformatics applications. This article, the first in a series, introduces Leafcutter, a new product designed to make this possible.

About the Software

Leafcutter is a framework consisting of reusable Swing components and supporting libraries for building chemically-enabled user interfaces. Based on ChemWriter, Leafcutter will contain most of the functionality of the 2D structure editor, but packaged as a set of highly customizable components. Whereas ChemWriter consists of configurable but finished applets for editing and rendering, Leafcutter will consist of components that can be used to build entirely new applets, desktop applications and other Rich Clients.

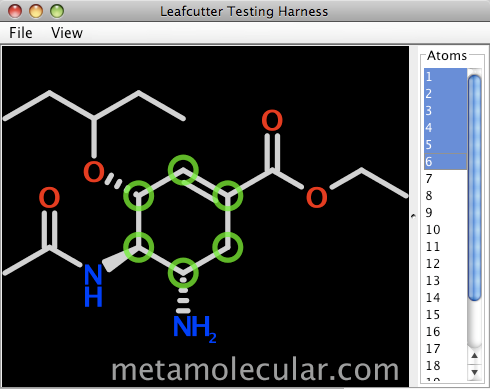

An alpha-stage developer preview is now available by request from Metamolecular. The package contains API documentation and source code for a sample Swing application (shown below).

The design constraints for tools used to build custom chemically-enabled user interfaces can vary significantly, but fine-grained control over appearance and behavior are top considerations. Depending on the specific use, controlling deployment footprint can also be critical. Leafcutter's design and implementation will address these needs uniquely.

What's New Here?

Although Leafcutter can be used to build traditional Cheminformatics applications, its main purpose will be to enable new kinds of applications that speak the language of 2D chemical structures natively.

Many of today's cheminformatics applications accept 2D chemical structures as input and render the same as output. But they're not generally designed to combine 2D chemical structures with their associated information in an interactive way.

For example, consider "Retro," a hypothetical application that enables Curt, a synthetic chemist, to plan his next synthetic route. Curt would draw his target molecule into a ChemWriter-like editor, as is typical for most reaction databases. But unlike other applications, Retro would interactively give Curt information about possible synthetic routes.

Clicking on a bond displays a side panel summarizing the number of published synthetic procedures that might be applicable. Clicking on the "Accept" button makes the bond disconnection and records the procedure hitset for later retrieval. Clicking on a "Suggest" button, highlights bonds representing viable disconnections, some of which might not have occurred to Curt otherwise.

Most synthetic organic chemistry databases are designed to be maps; Retro is designed to be a GPS device. A recent talk at the San Diego section of the ACS by Jun Xu offered some useful insight into the difference between these two approaches.

In addition, Curt communicates with Retro in his native language, the language of 2D chemical structures, by drawing, pointing and listening. It's the same way he communicates with his colleagues about chemistry.

The same concept could be applied to areas as diverse NMR and IR spectrum assignment and query, mass spectrometry, analyte detection, molecular mechanics calculations, and teaching reaction mechanisms.

Conclusions

If you plan to develop custom user interfaces that draw or manipulate 2D chemical structures, regardless of their design, Leafcutter will provide a powerful new tool for doing so.