How to Find Chemical Information on the Internet: Why Open Source, Open Access, and Open Data Matter

The Web may be the most effective information-delivery platform ever created. Unfortunately, a variety of barriers, both technical and cultural, restrict the use of the Web for chemistry. In the last few years, three powerful forces for change have emerged: Open Source; Open Access; and Open Data. Most of what's written on these subjects takes a theoretical angle that makes it difficult to visualize real benefits. In this article, I'll discuss these ideas from a much more practical perspective.

A Thought Experiment

Try this simple thought experiment: using only a browser and the free Internet, find all Web pages pages that have anything scientifically-relevant to say about your favorite molecule. How would you do it?

It's Trivial

If you were lucky enough to have chosen a molecule with a trivial name such as 'caffeine', you could just try Google. Google's first result would link you to the Caffeine Wikipedia article. Wikipedia is an evolving phenomenon that, according to some critics, will never have a place in scientific research. It may not be ready now, but reading the meticulously annotated and cross-referenced entry for caffeine should make anyone who would say "never" at least a little nervous. Many of the citations in Wikipedia's caffeine article point to the primary scientific literature through PubMed.

The remainder of Google's top-50 results are general audience items unlikely to interest a scientist keeping his or her nose to the grindstone: companies that sell caffeinated products; a variety of FAQs; self-help medical articles; and of course, this one. We shouldn't be surprised. In the eyes of a massive search engine like Google, chemistry is just one of many niche markets.

Adding terms to our Google search might produce more targeted results. For example, what if we wanted to find a proton NMR spectrum of caffeine? We could type "caffeine proton nmr" into Google. The first result links, indirectly, to an article in the subscription-only Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A. This does us no good because we have no subscription, limited funds, and no access to the journal at a library. The second link is a direct hit: the proton NMR spectrum of caffeine in water-formic acid. Significantly, the information is contained in a peer-reviewed article (DOI) published by the Japanese Open Access journal, Analytical Sciences. The fact that Analytical Sciences is an Open Access journal has made a world of difference in our search.

Although this might seem like the perfect solution, recall that the goal of the experiment was to locate all scientifically-relevant online content relating to the molecule. The technique we just used is most likely to succeed when we want specific information about molecules with a single trivial name. Even then, many resources may not cite a trivial name at all.

The Real World

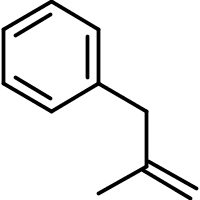

Our options are even more limited when it comes to comprehensively text-searching even the simplest molecules lacking a widely-used trivial name. For example, consider the molecule represented by the systematic name '3-phenyl-2-methylpropene.'

If we were using a proprietary system such those offered by Chemical Abstracts Services (CAS), we could simply enter the structure into a client and read off our results. This works because CAS isn't matching text when a query is submitted. Instead, it's matching molecular structures that have previously been encoded by both humans and machines.

The minute we step out of the orderly system created by CAS and into the chaos of the Internet, we confront a thorny problem. In practice, there are only two widely-used methods to convert a molecular structure diagram into a form that can be text-searched, and each has major limitations:

- IUPAC Nomenclature This method has the advantage of being Open. It suffers from the complexity of its encoding rules, resulting in a variety of nonstandard implementations. As a result, it's possible to find multiple phrasings of the same IUPAC name, reducing its use as a unique identifier.

- CAS Numbers This method replaces a standard encoding system with a central registration authority. The advantages are that the representation of the identifier itself is unambiguous. Conversely, the meaning of a CAS Number can only be known by referring to a registration authority. Unfortunately, the current business model for CAS is based on restricting information flow, rather than promoting it.

Search by IUPAC Name

Let's try searching Google for IUPAC nomenclature. Entering '3-phenyl-2-methylpropene' produces a results page containing three unique entries. One of them links to a database run from the University of Hamburg. I gather the purpose of this database, which I was unaware of before doing this search, is to link to Landolt-Börnstein Online, a collection of numerical data. Interestingly, a search for data on a single compound turned into the discovery of yet another free chemistry database.

The remaining hits from the Google search linked to two pages (pdf, pdf) from ACS journals. The ACS routinely makes the first page of its articles a free download. It's interesting to note that these were the only ACS hits returned by Google.

We've exhausted the possibilities with our chosen IUPAC name and Google. But before moving on to searching by CAS Number, we need to solve a problem. How do we get the CAS number for our compound?

Finding a CAS Number: A PubChem Detour

Concisely summarizing what PubChem does can be difficult because different users will emphasize different aspects of its design. For our purposes, PubChem probably contains a Web page describing the compound we've been researching, and on that page may be a CAS number.

Submitting our molecule to PubChem's search page produces one result. Fortunately, this page lists our compound's CAS number: 3290-53-7.

Search by CAS Number

Submitting our CAS number to Google produces sixteen results. The first two link to the Landolt-Börnstein pages. The next result links to a product listing page for a chemical supplier.

The fourth result links to a far more interesting page - the Organic Syntheses website. Fortunately for us, Organic Syntheses makes its contents freely available online. Following the link takes us to a preparation in which one of the reagents can be substituted with our molecule of interest. Further down in this page, we can see that this molecule has been further cross-referenced. Two procedures are listed, one of which is new to us. Following the link, we find a complete synthetic procedure with full characterization and primary literature citations. Jackpot.

Organic Syntheses permits free public access, but is it Open Access? Many would say not, due to the fact that it retains full copyright to its works and doesn't permit free redistribution. The distinction mainly matters to those seeking to create Open Data repositories based on the contents of periodicals such as Organic Syntheses. To an end user, however, the distinction matters little in the short run.

The remaining results from our Google search are interesting, but mainly consist of chemical supplier catalogs. It should, however, be noted that all of the results returned by a Google search of our CAS number were relevant to our molecule of interest.

InChI

In an effort to overcome the limitations of CAS Registry Numbers and IUPAC systematic nomenclature as unique molecular identifiers, a new system has recently been introduced, the IUPAC International Chemical Identifier (InChI). In contrast to a CAS number, an InChI can be assigned independently of a central authority. Like systematic nomenclature, an InChI can be decoded to a molecular representation. Unlike IUPAC systematic nomenclature, an InChI is generated by a computer algorithm far too complicated for human use. The developers of the InChI software have released their work under an Open Source license, promoting its widespread use by ensuring that services like PubChem will have no difficulties integrating InChI with their software infrastructures. Unlike either CAS Numbers or IUPAC names, InChIs are not yet in widespread use, a point which currently limits their utility.

The PubChem page for our search molecule listed an InChI, as do all PubChem Compound Summary pages. As shown by Peter Murray-Rust and others, it is perfectly feasible to use Google to search for InChIs. Let's try.

Submitting our InChI query to Google gives no results. Leaving off the leading 'InChI=' text, as briefly mentioned here, also results in no hits. This tells us that Google has found no instances of our InChI, and that Google still does not crawl PubChem Compound Summary pages.

Use a Free Database

Numerous free chemistry databases are now running on the Internet. For example, a recent article highlighted thirty-two of them. Would one of them be useful to our search? We need to ask ourselves if we really want to perform more than thirty individual searches. What if we were looking for data on several molecules? Nothing would prevent us from doing this in theory, but in practice, this is too much work.

What we'd really like is to submit a structure query to a single service that will query all of these free databases for us. While such services do exist in name, their breadth is restricted. A more comprehensive solution would be very helpful indeed.

Conclusions

The Web's convenience and ubiquity have prompted many calls for greater Web accessibility to public chemical information. As hinted at by the examples in this article, Open Source, Open Data, and Open Access are three interrelated forces that can make this vision a reality. Open Access journals lower the economic barriers to compiling Open Data sources. Making these Open Data sources useful to scientists in a cost-effective way requires Open Source software. The availability of good Open Source software stimulates the creative combination of Open Data sources. And so on.

A lot needs to be done before this positive feedback loop can replace the status quo. But even with the chaotic, balkanized system that now exists, the benefits are plain to see. With even a small amount of coordination among Open Source software developers, Open Data providers, and scientific publishers, the most amazing things could happen.