A Molecular Language for Modern Chemistry - Cisplatin, Transplatin, and Molecular Configuration

Recent articles have discussed FlexMol as a new language capable of representing many of today's most difficult molecules: metallocenes; axially-chiral biaryls; and other forms of axial chirality. FlexMol can also encode more common molecular features such as E/Z alkene geometrical isomerism. So far, discussions of stereochemistry have been limited to molecular conformation. In this article, I'll demonstrate how FlexMol encodes molecular configuration, using cisplatin and transplatin as examples.

The Difference Between Configuration and Conformation

FlexMol's distinction between configuration and conformation is a simple one: if two isomers can't be interconverted by bond rotations, then configuration is used to describe them. Otherwise, conformation is used. The geometrical isomers of dichlorodiamino platinum fall into the former category. For more rigorous definitions, see Dietz' original specification on which FlexMol is built.

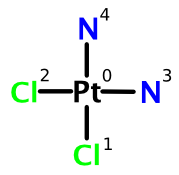

Cisplatin

Cisplatin consists of a central platinum atom surrounded by two chloro ligands and two ammonia ligands arranged at the corners of a square. Using the numbering system present in the structure above, we can construct a complete FlexMol representation. Rather than reproduce the entire document here, I'll just highlight the stereochemical aspects. In contrast to the other FlexMol examples covered on Depth-First to date, this example contains a configuration element:

<!-- snip -->

<configuration>

<configurationWheel>

<atomPair source="Pt0" target="N4"></atomPair>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="Cl2"></center>

</halfPlane>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="N3"></center>

</halfPlane>

</configurationWheel>

<configurationWheel>

<atomPair source="Pt0" target="N3"></atomPair>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="N4"></center>

</halfPlane>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="Cl1"></center>

</halfPlane>

</configurationWheel>

<configurationWheel>

<atomPair source="Pt0" target="Cl1"></atomPair>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="N3"></center>

</halfPlane>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="Cl2"></center>

</halfPlane>

</configurationWheel>

<configurationWheel>

<atomPair source="Pt0" target="Cl2"></atomPair>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="Cl1"></center>

</halfPlane>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="N4"></center>

</halfPlane>

</configurationWheel>

</configuration>

<!-- snip -->

Notice that the most of the subelements of cisplatin's configuration were also used in the context of conformation. The three main differences are:

- The element

configurationWheelis used in place ofconformationWheel; - Instead of a

gammaSequenceeach chiral axis is described by anatomPaironly; - There are as many

configurationWheelsas neighbors on a configurational atom. In this case, platinum is the configurational atom. It has four neighbors, and so fourconfigurationWheelsappear. Each neighbor is in turn placed at thetargetof the chiral axis.

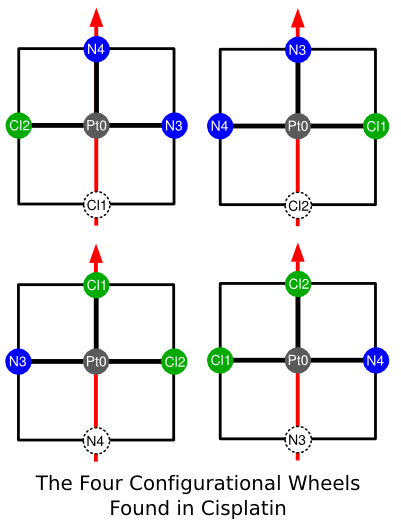

To better visualize cisplatin's configuration, consider the four diagrams below, each of which represents one configurationalWheel. Given the cisplatin's square-planar geometry, each "wheel" in this case consists of only two opposing halfPlanes.

There are a few things to notice. First, each configurational halfPlane is divided into three sections: lower; upper; and center. A center designation means that an atom sits precisely on the line bisecting a given half-plane. As with conformational half-planes, upper means the part of the half-plane closest to the axis endpoint; lower means the part of the half-plane furthest from this atom. Second, notice that an atom oriented 180 degrees from the direction of the chiral axis is not assigned to a halfPlane because it occupies none. As we shall see, this is not a limitation.

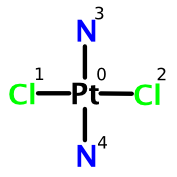

Transplatin

How does this system allow us to distinguish cisplatin from transplatin? Given the atom numbering as shown above, we can construct the complete FlexMol representation. The configuration element is shown below:

<!-- snip -->

<configuration>

<configurationWheel>

<atomPair source="Pt0" target="Cl2"></atomPair>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="N3"></center>

</halfPlane>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="N4"></center>

</halfPlane>

</configurationWheel>

<configurationWheel>

<atomPair source="Pt0" target="N3"></atomPair>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="Cl1"></center>

</halfPlane>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="Cl2"></center>

</halfPlane>

</configurationWheel>

<configurationWheel>

<atomPair source="Pt0" target="Cl1"></atomPair>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="N3"></center>

</halfPlane>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="N4"></center>

</halfPlane>

</configurationWheel>

<configurationWheel>

<atomPair source="Pt0" target="N4"></atomPair>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="Cl1"></center>

</halfPlane>

<halfPlane>

<center atom="Cl2"></center>

</halfPlane>

</configurationWheel>

</configuration>

<!-- snip -->

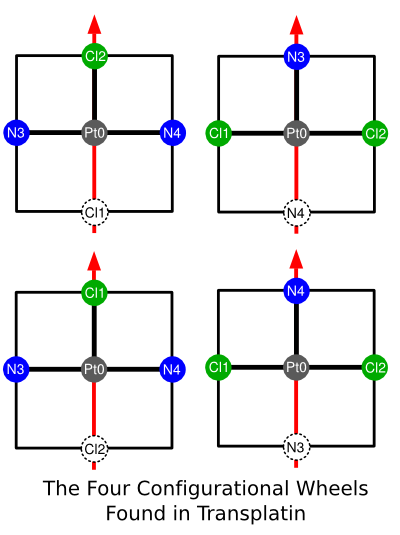

The arrangement of planes can be represented by the diagram below:

As you can see, the cisplatin and transplatin configurations are clearly distinguishable by inspection. Notice that we have not resorted to chiral flags, atom parities, or any form of stereochemical template. When a new atom geometry is desired, for example trigonal bipyramidal, octahedral, t-shaped, or otherwise, exactly the same rules apply.

A Software Implementation

It's not difficult to write software designed to compare stereochemical configurations in the same way as it is done manually. For example, this has been fully implemented in Octet.

So What?

At least one other language shares FlexMol's ability to encode square planar stereochemistry: SMILES. The difference is that FlexMol uses no templates, resulting in a rule-based, extensible language. SMILES, on the other hand, uses chiral templates. If your molecule doesn't fit one of these pre-defined templates, you can't encode its stereochemistry with SMILES and expect a third party to be able to understand it. This is the unavoidable consequence of a template-based stereochemistry encoding system such as the one used by SMILES.

Conclusions

FlexMol offers a completely new way to think about encoding stereochemistry with computers. The method is both flexible and systematic. It does away with the need for inherently confusing and limited constructs such as atom parities, chiral flags, and stereochemical templates in favor of actually describing the stereochemical environment of atoms in a molecule. One stop remains on this introductory tour of FlexMol and stereochemistry: tetrahedral chirality.