SMILES and Aromaticity: Broken?

Since its introduction in 1988, the Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) has become one of the most widely-used molecular encoding systems in cheminformatics. But all technologies, no matter how widely-used, can be improved, and SMILES is no exception. This article, the first in a series, discusses a particularly thorny problem in the SMILES language.

A Little About SMILES

From the beginning, SMILES was a creative response to the complexity of the then-dominant Wiswesser Line Notation. This can be seen perhaps nowhere more clearly than in the introduction to Weininger's seminal paper on SMILES:

SMILES is a chemical notation language specifically designed for computer use by chemists. … Among several approaches to computerized chemical notation, line notation is popular because it represents molecular structure by a linear string of symbols, similar to natural language. The Wiswesser Line Notation is the most widely used representative of this method. It meets the essential requirements for a deterministic chemical notation, but it is difficult to use because many rules must be followed to generate the correct notation of a complex structure. To overcome this and other difficulties, the SMILES system was designed to be truly computer interactive.

What started out as a way for humans to more easily encode molecular structures has since evolved into a way for computers to encode molecular structures. Several factors are responsible for this shift, the biggest being the emergence of the Graphical User Interface, and with it, the chemical structure editor.

Today, few chemists know how to encode SMILES nor, understandably, do they want to.

But rather than dying out, SMILES found a new niche. Computers in the late '80's were mere toys; storage space was measured in kilobytes, and bandwith was practically nonexistent. But with a few ASCII characters, the complete connection table of most organic molecules could be encoded by SMILES. Not only this, but the algorithms needed to encode and decode SMILES were easy to reduce to practice in software. Daylight's original implementation of SMILES was soon joined by many others.

A de facto standard was born.

If It Ain't Broke, Don't Fix It

For the last twenty years, SMILES has been used with great success to encode and store molecular structures. In an industry with few standards, SMILES is a rare example that shows what might be possible.

If SMILES has been so successful, then what's broken that needs fixing?

Over the years, a growing list of missing, inconsistent, or confusing aspects of the SMILES language have come to light. One vendor of a SMILES implementation has even cataloged some of them. In most cases, the various implementers of SMILES systems have done the only thing they could do under the circumstances: apply their own judgment and best guesses.

The result has been the gradual introduction of subtle incompatibilities among the SMILES implementations currently in use. This is the problem that the OpenSMILES group aims to address.

This status quo works in an environment of information silos, proprietary code, and closed data. But as cheminformatics moves in the direction of open data and interoperability, the problems become painfully apparent.

Of all the topics that have been discussed so far by the OpenSMILES group, one stands out for its level of interest, number of contributors, strong opinions, and detailed discussion: lower-case atom symbols and aromaticity.

Aromaticity in SMILES

SMILES allows two kinds of atoms to be specified: upper-case and lower-case. Lower case atoms, according to existing documentation, signify 'aromatic' atoms.

Weininger made clear that the reason for introducing lower case atom symbols was to facilitate canonicalization and substructure recognition. From the original paper:

Aromaticity must be detected in a system that generates an unambiguous chemical nomenclature. As will be discussed in following papers, this is needed both for the generation of a unique nomenclature and for effective substructure recognition. There can be no definition of 'aromaticity' that is both rigorous and all-encompassing: the word implies something about 'reactivity' to a synthetic chemist, 'ring current' to a NMR spectroscopist, 'symmetry' to a crystallographer, and presumably 'odor' to the original user of the word. Our objective in defining aromaticity is to provide an automatic and rigorous definition for the purposes of generating an unambiguous chemical nomenclature. Although the SMILES algorithm produces results that most chemists find natural, nothing is implied by this definition about physical properties.

Kekule structures, in which double bonds and single bonds alternate, make it difficult for computers to implement certain kinds of algorithms. Defining lower case atom symbols to remove artificial asymmetry eliminated these problems.

Weininger's original paper then goes on to describe the criteria for aromaticity in the SMILES language. At it's core, aromaticity boils down to the following defintion:

… To qualify as aromatic, all atoms in the ring must be sp2 hybridized and the number of available 'excess' π electrons must satisfy Hückel's 4n+2 criterion. …

Seems simple enough, but even in 1988 things were not so clear. For just a few sentences later, Weininger continues:

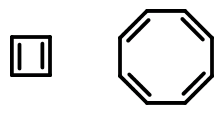

… Entries of c1ccc1 and c1ccccccc1 will produce the correct antiaromatic structures for cyclobutadiene and cyclooctatetraene, C1=CC=C1 and C1=CC=CC=CC=C1, respectively. … [emphasis added]

How are we to interpret this? Apparently, c1ccc1 and c1ccccccc1, neither of which obey the 4n+2 rule, are nevertheless valid SMILES. We can even use Daylight's Depict application to verify for ourselves that both c1ccc1 and c1ccccccc1 are read and depicted.

Perhaps the concept of "antiaromaticity" (in contrast to "non-aromaticity") holds a special place in the SMILES language. If so, this distinction has never been clarified.

While puzzling over the apparent contradiction, we later read that:

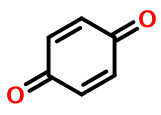

… For example, quinone is nonaromatic, with only four excess electrons.

Weininger goes on to imply that the only correct way to represent quinone in SMILES is without lower case atom symbols, for example:

O=C1CCC(=O)CC1

And still later:

… For example, if one of the benzene ring's electrons is removed to form c1ccc[cH+]1, this ion is not aromatic because there are only five π electrons. …

Ambiguity makes it impossible to write standardized software: either 4n+2 is the rule for triggering the aromatic flag, and therefore lower case atom symbols, or it is not. If exceptions to this rule are needed, they must be specified in enough detail to be reduced to practice. To my knowledge, no documentation written in 1988 or since then has provided the necessary guidance.

We can't have it both ways.

More Brokenness

Next, consider some of the examples left out of the original SMILES description. What about oligocyclic aromatics?

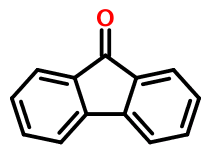

Fluorenone, according to the SMILES electron counting rules, has twelve π electrons and is therefore not aromatic. Strictly speaking, a SMILES like this:

O=c2c1ccccc1c3ccccc23

in which the carbonyl carbon is represented with a lower case atom symbol, should be considered invalid. Not just undesirable, but verboten.

Yet Daylight's own Depict program, and other SMILES implementations, treat it as valid.

Despite the lack of an aromatic tricyclic ring system, we may nevertheless want (or need) to represent fluorenone using lower case atom symbols. After all, canonicalization and substructure searches are very difficult otherwise.

So any software we write needs to peel back layers of the tricyclic ring system in a quest for isolated aromatic rings. This exercise is clearly chemically meaningless as all atoms are coplanar and sp2 hybridized, and therefore interact. The counterargument is that the SMILES aromaticity model has no basis in reality - it's just a convention. So we press on.

We eventually end up with a SMILES like this:

O=C2c1ccccc1c3ccccc23

The larger problem is making it clear when a reader or writer is and isn't allowed to perform this peeling back operation in search of aromaticity. Does the above SMILES match the SMILES definition of aromaticity or does it not? Are we allowed to peel back ring systems looking for imaginary 'embedded' aromatic ring systems or are we not?

The answer may exist somewhere, just not in the documentation I have access to.

The pragmatic approach, and the one taken by some implementations, is to simply ignore the whole question, forget about 4n+2, and call everything that 'looks' aromatic, like the fluorenone carbonyl carbon, 'aromatic.'

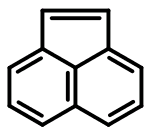

As another example, consider acenaphthalene:

c1cc2cccc3ccc(c1)c23

Based on the published 4n+2 rules for SMILES aromaticity detection, acenaphthalene's twelve π electrons mean that it can't be represented in the aromatic form. It's not just discouraged - it's not allowed. Yet the Daylight Depict program, and a few other SMILES implementations, will accept this input as valid.

The only way we can take advantage of the symmetrization afforded by lower case atom labels is to go hunting for isolated benzene rings. Upon doing so, we arrive at the following SMILES:

c1cc2C=Cc3cccc(c1)c23

Once again, we've more or less made an arbitrary distinction, assigning one set of carbons as aromatic and the other, fully coplanar, conjugated, and sp2-hybridized set as non-aromatic. Does the SMILES language allow us to do this? Again, the answer may exist somewhere, but not in any material I've been able to find.

To put it simply, where in the SMILES documentation are we informed of which atoms in a coplanar, fully conjugated and sp2 hybridized ring system can be ignored from the 4n+2 test?

For that matter, how do we know that oligocyclic aromatic ring systems are supported at all? Maybe only isolated five- and six-membered rings should be evaluated.

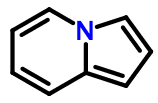

Consider pyrrolopyridine (depicted above):

c2ccn1cccc1c2

Now let's assume that the SMILES 4n+2 rule can only be applied to individual rings, not ring systems. This prevents us from writing a SMILES like the one shown above because the left-hand pyridine ring has a formal π electron count of 7 - two from each endocyclic double bond, two from the nitrogen atom, and one from the exocyclic double bond.

The best we could do is to write a SMILES like this:

c2cc1C=CC=Cn1c2

The only way we can create an 'aromatic' SMILES for the 4n+2 pyrrolopyridine ring system is to combine the electron counts for both rings.

But Daylight's own Depict system, and I suspect many others, imply that the fully aromatic version of the pyrrolopyridine SMILES is valid.

Once again, we can't have it both ways. If full ring systems need to be perceived and tested for 4n+2 π electrons, then consistency requires it also be done for acenaphthalene, fluorenone, and countless others for which space and time prevent discussion. If particular ring systems are exempt, then the SMILES language documentation should specify in detail how to tell the difference.

Conclusions

Given the problems in combining SMILES' symmetrization capability and lower-case atom symbols with the overloaded concept of aromaticity, one has to wonder - is it worth the trouble? Given the disregard for these rules by working third-party code, by Daylight, and by the original SMILES documentation, how reasonable is it to continue to use 4n+2 as the rule? What does the resulting confusion really buy?

There is a simple way to resolve the issue, but you're probably not going to like it - at least not at first. But that's a story for another time.