Everything Old is New Again - Wiswesser Line Notation (WLN)

Sometimes, searching through the attic of scientific ideas turns up unexpected treasures. Like old clothing styles that suddenly become fashionable again, the passage of time has a way of making old ideas relevant by supplying new context. Those ideas that once enjoyed widespread popularity followed by complete obscurity are especially interesting. This article talks about one of them and why it may matter again.

Some History

Wiswesser Line-Formula Chemical Notation (WLN) was the most popular of perhaps a dozen actively-used line notations systems during the 1960s and 1970s. Developed by William J. Wiswesser over a period of many years starting in the 1940s, WLN contains a surprising number of modern ideas about chemistry and information. At one point a serious contender for the position now held by IUPAC nomenclature, WLN has become so obscure that few chemists have even heard of it and no modern software can manipulate it. Even finding information on the basic grammar of WLN is difficult: almost all of this documentation is contained in out-of-print books.

A Guide

To my surprise, WLN is both easy to understand and easy to use. As far as canonicalized line notations go, WLN is far easier to comprehend than either InChI or Canonical SMILES. Even more surprisingly, WLN actually meets more than a few of the requirements for the ideal line notation for the Web. I was always struck by claims that high school graduates with little chemistry background could be trained to encode WLN in a few weeks; this now seems very plausible.

My guide is Elbert Smith's short 1968 book The Wiswesser Line-Formula Chemical Notation. I was able to pick up a used copy in excellent condition for under $30.00 from Amazon.

Some Examples

Functional groups, carbon chains, and rings play central roles in WLN. Unlike modern line notations that emphasize atoms, WLN is designed to mirror the way that chemists actually think about chemistry.

Consider acetone:

1V1

The two "1"s stand for saturated one-carbon chains, i.e. methyl groups. The "V" stands for a carbon doubly-bonded to oxygen.

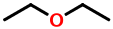

Given nothing more than the above example, the encoding of diethyl ether should be completely clear:

2O2

"O" simply stands for a divalent oxygen atom.

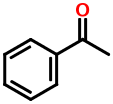

The benzene ring is one of the most ubiquitous functional groups in organic chemistry. Wiswesser knew this and wanted to make it easy to encode aromatic compounds. His solution is simplicity itself. Consider acetophenone:

1VR

The "R" stands for a benzene ring. WLN canonicalization gives it the lowest priority and this is why it appears last.

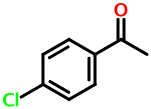

What about disubstituted aromatics? Consider 4-chloroacetophenone:

GR DV1

The "G" symbol stands for chlorine. The " DV1" stands for the 4-acyl substituent. Here, the "D" denotes the 4-postion. The 3- position would result in " CV1", and the 2- position would give " BV1". The space character means that the character following it should be interpreted as ring locant.

WLN uses a very simple system of canonicalization based on alphanumeric order. Priority increases in the direction: (1) symbols; (2) numbers in numerical order; and (3) letters in alphabetical order (with the exception of R which has lower priority than symbols). Coding generally begins at the substituent assigned the highest priority. This explains why 4-chloroacetophenone is not coded as "1VR DG".

Advantages of WLN

WLN is remarkably compact, especially when compared to SMILES and InChI. For example, consider the InChI for 4-chloroacetophenone, which is eight times longer than the corresponding WLN:

InChI=1/C8H7ClO/c1-6(10)7-2-4-8(9)5-3-7/h2-5H,1H3

Additionally, it's readily apparent to a human observer when a WLN is not properly coded - after all, the language was designed to be both read and written by humans rather than machines. Anyone can look at "GR DV1" and deduce almost instantly that it contains a carbonyl group (V), a phenyl group (R), a chloro group (G), and a methyl group (1).

And if this functional group recognition is easy for humans, it's orders of magnitude easier for machines. It's not difficult at all to imagine very sophisticated and fast molecular query systems that do nothing more than simple processing of the ASCII text contained within WLN strings.

Conclusions

It's very unlikely that WLN will ever be resurrected for the purpose of replacing existing line notations. On the other hand, WLN offers many potentially useful concepts for those creating new line notations. As they say, history doesn't repeat itself, but it frequently rhymes.