Name That Graph Revealed: Comments, Peer-Review, and the Web

Nothing stimulates quality discussion in science like numbers. The numbers themselves don't even need to be initially accurate or properly obtained - those things work themselves out in the end. Numbers simply offer a basis on which to form a hypothesis, which leads to re-analysis of the numbers, further data collection, and ultimately a more accurate picture of the phenomenon.

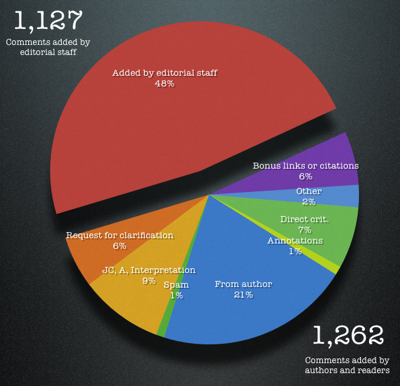

It's in this spirit that I reveal the source of yesterday's Name that Graph challenge: an analysis done by Nascent, (Nature's blog on Web technology and science) on the comments posted to the research articles appearing in the Public Library of Science (PLoS).

From the study:

- 18% of PLoS ONE papers have reader or author submitted comments

- 39% if you count comments added by editors (usually reviewer's comments)

- Very few comments are of the 'omg, wow' variety (as opposed to comments on blogs - this one excepted, obviously)

- authors are responsible for a high percentage (~ 40%) of user submitted comments

- 17% of user submitted comments contain interpretation or journal club style precis

- 13% of user submitted comments are direct criticism

- 11% are direct questions or requests for clarification

- These %s are similar to what we saw in the BMC dataset

- The trackbacks protocol is inadequate for picking up blog chatter about papers

PLos is one of the few scientific journal families to directly associate user comments with articles. To my knowledge, the only chemistry-related journal to do the same is the relatively new Journal of Cheminformatics.

There has been a great deal of recent discussion on the topic of scientific publication, peer-review, and the role comments might play in the process. Perhaps ironically, most of this discussion is happening on individual blogs and Friendfeed.

The most recent round of discussion was touched off by Iddo Friedberg (credit: Joerg Wegner), although his aim was simply to discuss a recent PLoS One paper on cell signalling using photons. Iddo could have posted his comments to the PloS One site itself, but instead chose to post them through Friendfeed. Many of the reponses related to that topic rather than the content of the paper.

A Friendfeed user going by the handle of genereg created a separate Friendfeed discussion on the topic of the lack of PLoS comments and why they don't seem to be used much.

The data collected by Nascent and others on the pattern of comments appearing in scientific journals offer some intriguing ideas for further exploration. For example, If editorial comments make up the bulk of commenting activity, what kind of information is being conveyed though them and how could this be accomplished more effectively?

These are still early days for science and the Web. Unlike many other segments of Web usage, science has a long tradition of the 'right' way to conduct peer-to-peer discourse. This is especially true in chemistry, where additional factors come into play. Nevertheless, the Web is a highly compelling platform for direct communication; the data on PLoS comments (and discussion around them) suggest that the best way to facilitate this direct communication may not have been created yet.

A major platform change is underway in which the Web is replacing paper in science. It seems unlikely that what worked for paper will work for the Web. It seems equally unlikely that what has worked for the consumer Web will work in all areas science.

The field is wide open, many big players are either stumbling or ignoring the changes taking place, and there's no consensus on how to proceed. Based on the numbers, what's your best guess?