Anatomy of a Cheminformatics Web Application: Structure Cleanup in Java Molecular Editor

A very useful feature of many 2-D structure editors is a "clean" function that tidies up bond lengths and angles. Java Molecular Editor (JME) is a lightweight 2-D editor that lacks this functionality. In this article, I'll describe a small Web application called "Cleanup" that adds a "clean" function to JME through Ajax and server-side programming, rather than directly extending JME itself. The technique described here differs somewhat from that described in a previous article on adding InChI support to JME with Ajax.

Cleanup in Action

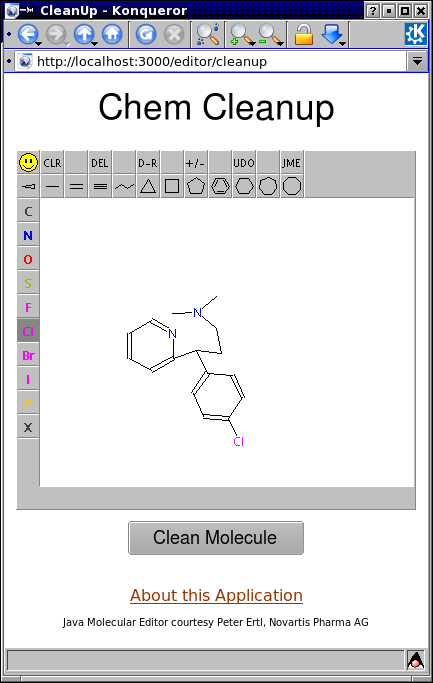

Let's say Bob needs to draw the structure of the H1 antagonist chlorpheniramine with JME. He mistakenly creates irregular bond angles at several points, but continues drawing anyway. His finished molecule looks like that shown below:

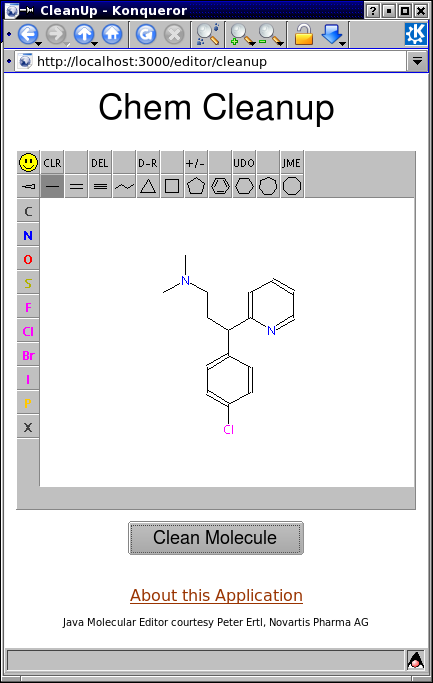

Rather than starting over to beautify his molecule, Bob, simply presses the Clean Molecule button. This produces a structure with much more aesthetically-pleasing atom coordinates:

If Bob needs to continue drawing at this point he can. In fact, he can press Clean Molecule as many times as he wants to clean his structure at any time. Each time he presses the button, his structure is retained within the JME window.

Download and Prerequisites

Cleanup requires Ruby on Rails and Ruby CDK. Both of these libraries can be installed using the RubyGems packaging system.

A recent article described the small amount of system configuration required for Ruby CDK on Linux. Another article showed how to install Ruby CDK on Windows.

The complete Cleanup source package can be downloaded from RubyForge. For convenience, a copy of JME is included with the distribution. The author, Peter Ertl, has kindly given permission for the bundled JME applet to be used with Cleanup. For other uses, consult the JME homepage.

Running Cleanup

After inflating the Cleanup archive, the following commands will start the server:

cd jme-cleanup-0.0.1

ruby script/server

AMD64 Linux users will need to prepend a LD_PRELOAD assignment to the script/server invocation. On my system, which uses Sun's JDK, this looks like:

cd jme-cleanup-0.0.1

LD_PRELOAD=/usr/java/jdk1.5.0_09/jre/lib/amd64/libzip.so ruby script/server

After starting the Cleanup server, pointing your browser to http://localhost:3000/editor/cleanup will run the application.

How It Works: A Web Application in Two Parts

Cleanup is a Web application consisting of two main parts - one written for a Web server, and one written for a Browser client. These two components work together to achieve an effect that, to a user, is indistinguishable from extending the JME applet with Java.

The first component consists of small Rails application that accepts a Molfile as input and produces a Molfile with re-assigned coordinates as output. A Rails Action, clean_structure accepts a Molfile encoded as form data and produces a response Molfile with re-assigned coordinates.

The second component of the Cleanup application is written in JavaScript and executed from within the Browser. Let's take a look:

/*

* Returns the client-specific version of XMLHttpRequest

*/

function createXHR() {

var xhr;

try {

xhr = new ActiveXObject("Msxml2.XMLHTTP"); // IE 5.0+

}

catch (e) {

try

{

xhr = new ActiveXObject("Microsoft.XMLHTTP"); // IE 5.0-

} catch (E) {

xhr = false;

}

}

if (!xhr && typeof XMLHttpRequest != 'undefined') {

xhr = new XMLHttpRequest(); // every other browser

}

return xhr;

}

function cleanStructure() {

var molfile = document.jme.molFile();

var xhr = createXHR();

xhr.open("GET", "clean_structure?molfile=" + encodeURIComponent(molfile));

xhr.onreadystatechange=function() {

if (xhr.readyState != 4) return;

cleanMolfile = xhr.responseText;

document.jme.readMolFile(cleanMolfile);

}

xhr.send(null);

}

As you can see, the client side of Cleanup consists of two JavaScript functions, createXHR and cleanStructure.

The purpose of createXHR is to return a valid instance of the central Ajax JavaScript object, XMLHttpRequest. This function is a standard idiom in Ajax programming, and many JavaScript toolkits eliminate the need to write it explicitly. The function is included here mainly for the purpose of illustration. Microsoft browsers define two different flavors of XMLHttpRequest, and both differ from the flavor supported by every other browser. To take this browser-specific behavior into account, a series of try/catch blocks are used.

The second function, cleanStructure does all of the JME-specific work. After obtaining an instance of XMLHttpRequest, a HTTP GET request is built from JME's molfile. Of course, the magic of this request is that it is asynchronous; it will not block the browser while it is being processed. When the request is complete, the cleaned Molfile is read by JME.

Through the coordinated action of both of Cleanup's components, the application gives the appearance that JME has cleaned its own structure.

So What?

Well-designed, rich functionality makes software interesting and useful. At the same time, users demand software that loads and responds quickly. Using the technique presented here, it's possible to satisfy both of these contradictory requirements. Delegating key tasks to a server obviates the need to transmit large Java libraries to clients. Instead, small Java libraries can be transmitted, and several small asynchronous requests will be processed along the way.

Viewed from this perspective, the capabilities of a good Java applet take on a very different character from what many have become accustomed to. In particular, extensibility and a robust, text-based communication protocol become much more important than built-in features.

For example, we could provide a much more consistent user experience if the Clean Molfile button were contained inside the JME editor itself, instead of on the Web page. In a more general sense, we'd like JME to offer the option of defining custom buttons that can be assigned arbitrary actions. Because Java/JavaScript integration is very well-supported, these custom actions could actually be written in JavaScript.

Conclusions

Java applets have been much maligned of late, partly due to the realization that in many situations they can be replaced with Ajax. However, well-designed, small, and extensible Java applets can play a key role in certain kinds of Ajax applications such as the one described here. Future articles in this series will explore some more of the many possibilities.