Electric Cars and Open Access

Markets are developed with fine products that customers desire to own. No salesman can take a marginal product into the marketplace and have any hope of establishing a sustainable consumer base. Consumers will not be forced into a purchase that they do not want. Mandates will not work in a consumer-driven, free market economy. For electric vehicles to find a place in the market, respectable products comparable to today's gasoline-powered cars must be available.

William Glaub, Chrysler Corporation

The value of scientific research - especially in chemistry - exists long after its publication and certainly well past 6 months. Moreover, it will be difficult to maintain a cost-efficient, high-caliber peer review and permanent archiving system if scientific societies have just six months to recoup costs before mandating free access. The prospect of “free” access to literature may seem good, but high quality literature at an affordable price is better.

The 2006 documentary Who Killed the Electric Car? should give anyone involved with Open Access reason to ponder. The film tells the story of GM's electric car experiment (the EV1) in California and its eventual failure. Open Access bears a striking resemblance to the electric car, including the ways parties on both sides frame the discussion, the market dynamics involved, and steps by government to mandate a solution. Can Open Access avoid the fate of the EV1?

In August 2005, the Beilstein-Institut launched Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry (BJOC). It was the first Open Access journal in chemistry to have the backing of a large publisher, and understandably, expectations were high. The journal's aims represent a significant departure from established practice in chemical publishing:

Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry offers organic chemists a unique opportunity to publish their research rapidly in an Open Access medium that is freely available online to researchers worldwide. In doing so it not only offers authors uniquely wide visibility and high impact, but it also ensures that their work is part of the permanent, publicly available archive of science. Open Access does not compromise the high quality of the articles published. All manuscripts submitted to the journal are subject to rigorous peer review.

While rigorous peer review has always been an objective in chemical publication, the idea of creating a permanent, publicly-available Open Access archive had only previously been attempted by a few daring, lesser-known publishers. Even more provocatively, BJOC waived its author submission fee, making the journal free to readers and authors alike.

Back in 2005, many were asking tough questions about the BJOC revenue model. How will BJOC maintain high publication quality while taking money from neither subscribers nor authors? Who will eventually end up paying for this service and when?

The question less frequently asked is the subject of this article: "Will BJOC be able to attract the same flow of high-quality manuscript submissions as its competitors?" The answer seemed so self-evident as to border on the absurd. Of course they would! Scientists everywhere seemed to be calling for Open Access, and here stood a publisher offering it at no cost to subscribers or authors - at least for a while. What was there not to like?

Fifteen months later, discussions of cost and quality, although no doubt important, are nowhere to be found. Whereas originally BJOC maintained that authors' fees would be waived for an indefinite period of time, their position now suggests that authors' fees might never be charged:

The publication costs for Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry are covered by the journal, so authors do not need to pay an article processing charge.

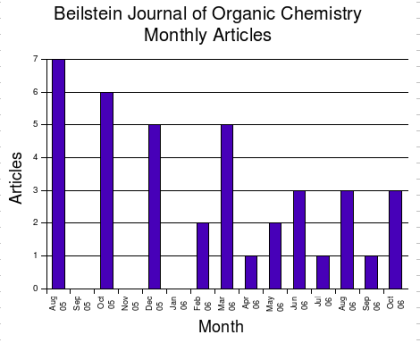

Anyone who has watched BJOC's front page for the last few months will no doubt have noticed a puzzling trend: the journal releases on average fewer than three papers per month, which actually represents a slight decrease from its rate at launch.

We can only assume that BJOC's editors didn't set out to produce a journal that publishes fewer articles in an entire month than Journal of Organic Chemistry publishes in a day. It then follows that publication-quality manuscripts are simply not being sent to BJOC in significant quantity.

We could certainly propose a few hypotheses at this point. For example, Peter Murray-Rust points to the "citation economy" and the role a journal's prestige plays in an author's journal selection process. He also points out that most journals take time to develop, and so it may be too early to judge the success of BJOC.

It would be hard to deny the role of prestige in scientific publication - but if this is the only explanation, then how do new journals ever come into being? It wasn't too long ago that Organic Letters was an upstart in a market long dominated by Tetrahedron Letters. Within two to three years, the tables had turned decisively. Consider also Chemistry: An Asian Journal. Although only a few months old, it out-publishes BJOC by a factor of 10:1.

Metcalfe's law states that in any communications network, among which scientific journals can clearly be counted, the value of the network is proportional to the square of the number of users. Large, existing journals have a significant advantage in this respect. A journal without regular readers can't possibly hope to attract manuscript submissions, no matter how revolutionary its publishing model.

I won't be offering any concrete hypotheses at this point. I'll simply return to the analogy I started this article with: the documentary Who Killed the Electric Car?. How could a car "supported" by apparently so many fail to find a market? The documentary names several possible factors, including the government, consumers, the auto industry, inferior battery technology, and alternative technologies. These factors no doubt played roles in the failure of the EV1, but maybe there's another way to look at it.

A very different kind of analysis of the failure of the electric car is provided in Clayton Christensen's landmark book The Innovator's Dilemma. Christenson views electric cars as a "Disruptive Technology", the defining characteristics of which are:

- It performs worse in one or more areas, but is typically simpler, more reliable, or more convenient than existing technologies.

- Its performance trajectory is steeper than that of existing technologies.

- It is built from off-the-shelf components.

- It is less profitable than existing technologies.

- Leading firms' most profitable customers generally can't use it and don't want it.

- It is first commercialized in emerging or insignificant markets.

- Large organizations are fundamentally incapable of successfully bringing it to market.

According to Christensen, the electric car died because GM failed to recognize that it was dealing with a Disruptive Technology and act accordingly. Could it be that the less than enthusiastic reception to BJOC results from the same failure on the part of the Beilstein-Institut? Future articles will explore this idea.